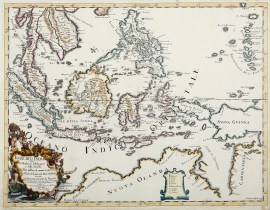

Striking 17th century engraved map by Vincenzo Coronelli showing the northern half of Australia.

Coronelli created this important map at a time when European powers were still assembling fragmentary knowledge of the southern hemisphere; this map embodies both the scientific curiosity and speculative imagination of late Baroque cartography.

Coronelli, a Venetian Franciscan friar, cosmographer to the Republic of Venice, and founder of the Accademia Cosmografica degli Argonauti, was among the most erudite geographers of his age. His Het Niew Hollandt forms part of a wider project to reconcile empirical observation with the philosophical ideal of a universal geography. At the end of the c.17th, European understanding of “New Holland” derived from earlier Dutch exploration. Voyages by Dirk Hartog in 1616, Abel Tasman in the 1640s, and other navigators of the Dutch East India Company had traced sections of the western, northern, and southern coasts, while the eastern seaboard and the interior remained unknown. Coronelli’s map synthesises this limited data with remarkable lucidity. Incorporating Tasman’s discoveries and earlier Dutch routes, it preserves the contours of Terra Australis Incognita, a lingering symbol of both scientific hypothesis and poetic mystery.

Engraved in Venice with Coronelli’s characteristic precision, Het Niew Hollandt displays the graceful ornamentation that distinguishes his Atlante Veneto and his celebrated globes for Louis XIV. Decorative cartouches, maritime figures, and baroque embellishments frame a carefully structured geography, merging accuracy with grandeur. The Dutch title unusual for an Italian mapmaker acknowledges the Dutch primacy in Pacific exploration and reflects Coronelli’s cosmopolitan reach within the international networks of geographic exchange. Beyond its aesthetic appeal, Het Niew Hollandt reveals Coronelli’s position at the threshold between Renaissance speculation and Enlightenment empiricism. His restrained depiction of the continent’s unknown interior, and the tentative rendering of certain coastlines, mark an early expression of cartographic caution and intellectual honesty. Rather than filling the void with conjecture, Coronelli leaves space for the imagination, a gesture both scientific and poetic that mirrors Europe’s evolving encounter with the antipodes.

In a wider historical sense, the map signifies Venice’s participation in global discovery despite its waning maritime influence. Coronelli’s connections with Jesuit scholars and foreign trading companies allowed him to gather and reinterpret information from across Europe, transforming it into a unified vision of the world. Het Niew Hollandt thus reflects not only the geography of Australia but also the geography of knowledge itself, a testament to the circulation of ideas in the early modern age.