Stands among the most influential figures in the history of geography and cartography. Born in Rupelmonde, Flanders, in 1512, and educated at the University of Leuven, under the mathematician and cosmographer Gemma Frisiu. Mercator transformed the art and science of mapmaking in the c.15th. His name became synonymous with the projection that reshaped the representation of the world—the Mercator Projection—yet his intellectual legacy extends far beyond a single technical innovation. A polymath steeped in Renaissance humanism, classical scholarship, theology, and mathematics, Mercator sought to reconcile the empirical precision of new discoveries with a cosmological vision grounded in divine order. His work bridged the medieval and modern worlds, integrating geography, cosmography, and theology into a unified epistemology that profoundly influenced European thought.

From his earliest works, Mercator demonstrated both technical mastery and philosophical ambition. His 1538 world map, one of the first to employ the name “America” for the New World displayed a strikingly modern sense of global unity, even as it retained geographical uncertainties characteristic of the age. His dedication to empirical accuracy coexisted with a deeply theological worldview, a tension that would define much of his intellectual trajectory. The religious and intellectual ferment of the Reformation profoundly affected Mercator’s generation. His private study of Scripture and affinity for humanist theology led to suspicion from ecclesiastical authorities, and in 1544 he was arrested by the Inquisition on charges of heresy. Though released after seven months’ imprisonment, the episode marked a decisive turning point. Mercator left Leuven and settled in Duisburg, in the Duchy of Cleves a centre of religious tolerance and humanist learning where he could pursue his cosmographical studies free from persecution. Mercator’s faith remained central to his intellectual outlook. He conceived the study of geography as a form of devotion, a way to discern divine order within the material world. His later works the Chronologia (1569) and the monumental Atlas sought to integrate geography, history, and theology into a single, comprehensive vision of creation. This intellectual synthesis reflected the broader ambitions of Renaissance humanism, which united empirical inquiry with spiritual and moral reflection.

Mercator’s most enduring contribution came with his Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata of 1569, the map that introduced what became known as the Mercator Projection. Designed primarily for navigators, it represented a breakthrough in the mathematical projection of the globe onto a flat surface. By increasing the spacing of parallels of latitude toward the poles, Mercator created a projection in which lines of constant compass bearing (rhumb lines) appeared straight, allowing sailors to plot courses more easily. The innovation was revolutionary, yet not without compromise: areas near the poles were greatly exaggerated in size. In privileging navigational functionality over spatial proportion, Mercator shifted the conceptual purpose of maps from representing the world as it “is” to providing an operational model for human action within it. His projection thus embodies the emerging scientific worldview of the early modern period, where mathematical abstraction became a tool for mastery of the natural world.

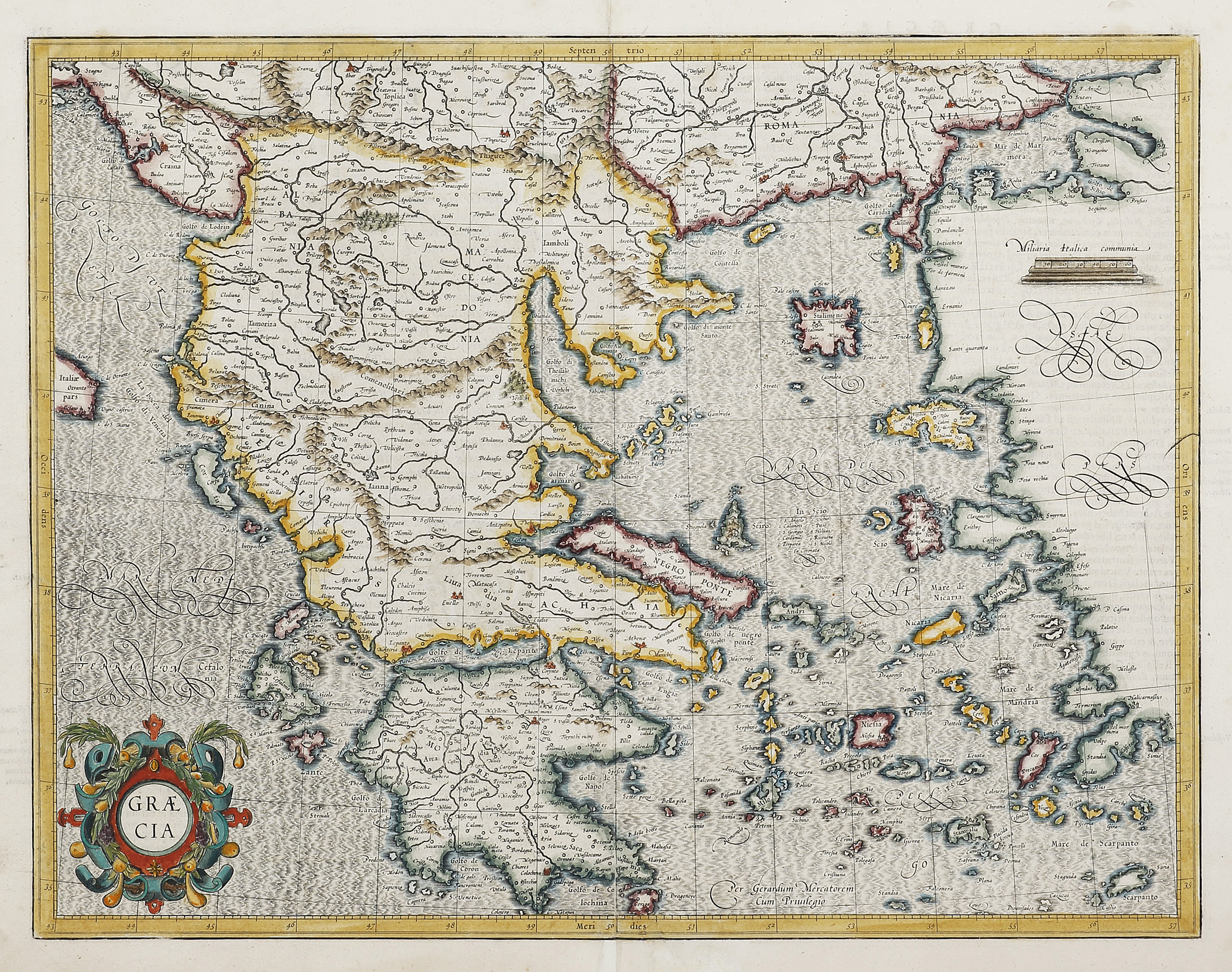

In the final decades of his life, Mercator turned to his grand cosmographical enterprise: the Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (“Atlas, or Cosmographical Meditations upon the Creation of the Universe and the Universe as Created”). The first volume appeared posthumously in 1595, published by his son Rumold Mercator. The work introduced the term “atlas” to denote a systematic collection of maps, derived from the mythic figure Atlas, whom Mercator regarded as a symbol of philosophical contemplation. Mercator’s Atlas was conceived not merely as a geographical compendium but as a theological and philosophical meditation. Its prefatory essays on cosmology and universal history reveal his ambition to portray the earth as part of a divinely ordered creation. The arrangement of maps from the heavens to the world, then to Europe and individual countries mirrors the descent from universal to particular, reflecting a scholastic conception of order suffused with Renaissance humanism.

Mercator’s legacy extended far beyond his own century, his projection became the foundation of nautical charting for centuries, shaping European exploration and colonial expansion. The Atlas inspired later works, most notably Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570), often regarded as the first modern atlas. Yet Mercator’s legacy was not just purely technical. His synthesis of mathematical precision and theological cosmography embodied the intellectual transition from the medieval to the modern worldview. By reconciling divine order with empirical observation, Mercator laid the groundwork for later thinkers such as; Kepler and Galileo to Descartes who sought to describe the universe in mathematical terms without abandoning its metaphysical dimensions. His cartographic methods became the visual language of global modernity, through which the world could be measured, divided, and understood.

Gerard Mercator’s genius lay not merely in innovation but in synthesis. His life’s work unified faith and science, mathematics and art, theology and geography, in a single vision of ordered creation. The 1569 projection redefined navigation; the Atlas redefined cosmography. Both works epitomise the Renaissance conviction that knowledge of the world was a form of reverence for its Creator. In bridging the divide between medieval scholasticism and modern empiricism, Mercator transformed not only cartography but also the intellectual map of European thought. His enduring influence rests in the idea that to map the world is to seek meaning within it—a pursuit as spiritual as it is scientific.

Bibliography;

-

Crane, Nicholas, Mercator: The Man Who Mapped the Planet (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002).

-

Brotton, Jerry, A History of the World in Twelve Maps (London: Allen Lane, 2012).Keuning, Johannes, “The History of Geographical Map Projections until 1600,” Imago Mundi, 12 (1955), 1–24.

-

Dekker, Elly, Globes at Greenwich: A Catalogue of the Globes and Armillary Spheres in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

-

Shirley, Rodney W., The Mapping of the World: Early Printed World Maps, 1472–1700 (London: Holland Press, 1983).

-

Snyder, John P., Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

-

Woodward, David, ed., The History of Cartography, Vol. 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).